We talk a lot about new development on this blog, and Philly sure does have a lot of it, but what about spaces in the city that are not under development? Places that sit, and have sat, unused and dilapidated for quite some time. I mean, we’re an old city and we’ve got some baggage: old garages, warehouses and lots that sit abandoned, either literally or practically, by their owners in struggling and vibrate neighborhoods alike. Well, if you’re anything like me, you find it a positive thing, and a quite inspiring thing as well, to see street art (wheat pastes, graffiti murals, stencils, etc.) begin to take over these spaces. Street art, like that of Joe Boruchow.

Every morning on my way to work through Northern Liberties, I walk pass freshly minted condos and refurbished houses mixed with lively, ground floor businesses, but evey block or so there’s a space that’s just been left abandoned. With no signs of love or care, or development anytime soon, these spaces often become the canvases for Philly’s street artists, and I couldn’t be happier with that. So a few weeks ago I set out with Philly wheat paster, Joe Boruchow, as he put up some art around the town, and I asked him about what he does, why he does it and the reactions he’s got from doing it:

Conrad: When did you start wheat pasting, and did you always use the black and white cutout design that is now so ironically “you,” or did that style evolve from something else?

Joe: The black and white cutouts are an evolution from when I used stencils to make posters for my band, The Nite Lights. About eight years ago, as my technique improved, the stencils became too fragile to work with. I started to simply photocopy black paper cutouts and found that I was able to get a lot more coverage pasting and stapling these around town than I had with the stencils. And in the end you still retain a fine art object.

C: Did you go to school for art?

J: No. However, I have taken some “continuing education” classes in perspective and figure drawing.

C: Can you explain, a bit, the process of your work. Basically, what it takes to go from an idea on a sheet of paper to a wheat paste?

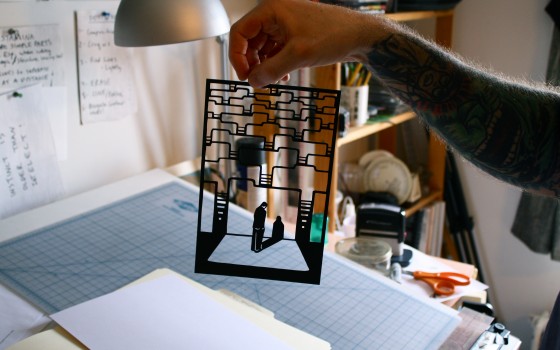

J:The process changes, as every new project is an adventure, but there are some things that are consistent. I’m always drawing little thumbnail sketches; from these I develop more detailed studies that I then redraw on black paper paying special attention to the limits of the medium. In a paper cutout all the black must connect (this makes things like belly buttons tricky). Then I excise all the white space with an Xacto blade, paint out the remaining pencil marks with black spray paint, and photocopy them. From these photocopies I have large prints made which I use for my paste ups.

C: What would you say inspires your art? One of my favorite pieces of yours lately was the one with the man standing helplessly in front of an endless wall of internet folders. (I can sadly say I relate to that feeling pretty often.) That one seems to have a pretty straight forward message, but you also have work that’s more abstract, either way, it’s easy to tell it’s yours. What inspires that great jump in content while at the same time keeping such a steady had on style?

J: I am inspired by the world around me, politics, the view from my studio and great art. One of the most exciting things about making paper cutouts is exploring how I can push the medium. I feel I have really found a voice with it. Depending on what I’m interested in at the time I can work abstractly or figuratively, satirically or decoratively. The finished piece is always stylistically distinct in part because of the medium, but also because of all the idiosyncrasies of my technique. I don’t think about style too much; if I made it, it’s going to look like I made it.

C: Where do you put up your work and why? What makes you choose one wall over another?

J: I’m always looking for good frames for my work. I find them everywhere I feel my art has context.

C: How do you feel about wheat pasting on abandoned property vs. privately own property ?

J: Most abandoned property is privately owned property. If they’re lucky enough for their building to be the site of my uncommissioned public art, they should be delighted.

C: Have you ever had any confrontations with police or neighborhood folks while putting up a wheat paste? What kind of reaction do you get from people who know you do street art?

J: Not with the police. I’ve been called a vandal a couple of times and had people tear them down in front of me. One person called me a “bully” responding to a piece that showed an impertinent Christ baby nursing (The Invasive Species Tondo). Mostly, though, people stop me to tell me that they appreciate the work and I thank them with a button or a poster. I never call myself a street artist, though. The term has taken on too much baggage. I prefer to be thought of as a folk artist.

C: What does your mom think?

J: My mother is, as always, very proud of her son.

C: Have you ever had gallery shows or participated in other, more traditional, mediums for showing your art? How do you feel these outlets help you to get your art out there compared to wheat pasting?

J: Absolutely. I love to show in galleries. It’s a chance for people to see the original cutouts from which the paste-ups are made. Their intricacy and smaller scale often surprise people, giving them a new perspective on the work. Plus, people who collect my original cutouts help to subsidize the more public and unremunerated aspects of my work.

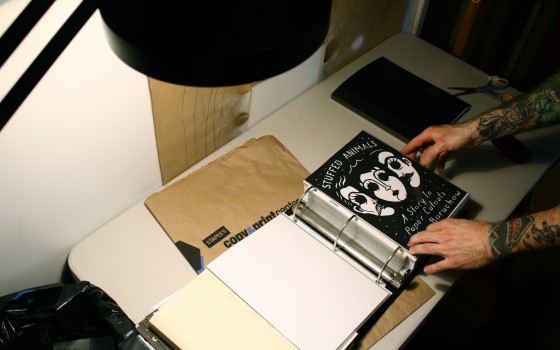

C: In 2010 you received a grant from the Xeric Foundation to create, “A Story in Paper Cutouts,” with Kettle Drummer Books. How did this come about, and what inspired the story?

J: The grant from the Xeric foundation was to publish not create Stuffed Animals: A Story in Paper Cutouts. That was the result of inspiration alone. It started in 2006 when I saw a taxidermied domestic dog in the front window of a South Philly home. I had a vague notion of the beginnings of a story and I began making one cutout at a time, simply making up the next scene as I went, until, at about page ten I came up with the rest of the narrative and scripted out the next ninety pages with quick thumbnail sketches. It took me four years to turn these into cutouts. On the suggestion and with the assistance of Lance Hanson (who had previously gotten a Xeric grant for his Don’t Cry) I submitted it to the Xeric Foundation and won a grant that funded its publication.

C: What would you or do you say to people who don’t approve of this art medium?

J: Some of it is worthy of your disapproval. But, since the dawn of man people have been putting images on walls. When it’s done well it can define your place and time.

You can purchase Joe’s graphic novel, “Stuffed Animals: A Story in Paper Cutouts,” from Kettle Drummer Books.